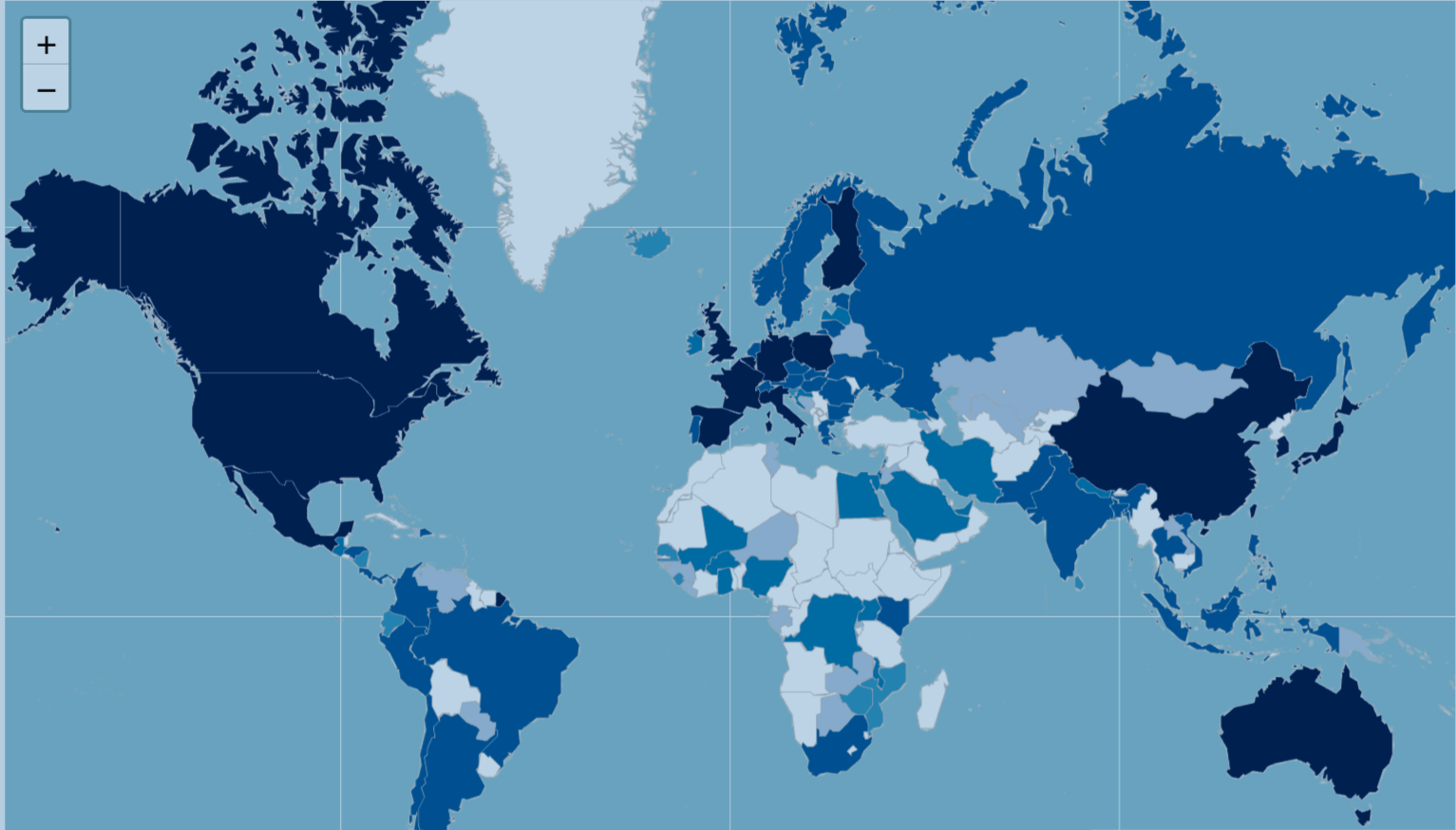

ClinicalTrials.gov is one of the most widely used clinical trial registries in the world. Biopharmaceutical companies, academic researchers, contract research organizations, patients—and increasingly AI companies—rely on it every day for insights, feasibility assessments, competitive intelligence, and training data.

Yet a crucial fact is often overlooked: the federal government does not verify the accuracy, completeness, or scientific quality of the information submitted to ClinicalTrials.gov [1]. Trial sponsors self‑report their data, and neither FDA nor NLM routinely audits entries for correctness or legitimacy. Compounding this challenge, ClinicalTrials.gov has evolved through decades of legislation—most notably the FDA Amendments Act of 2007 [2] and the Final Rule in 2016 [3]—resulting in shifting data requirements that many users are unaware of.

For those with deep experience in biomedical data, these caveats are expected. But for others—including AI teams scraping data directly from the registry—these nuances can create misinterpretation, flawed analytics, and in some cases, real‑world harm.

When Misinformation Reaches ClinicalTrials.gov

One well‑documented example involves unproven stem cell therapies [4]. Over the past decade, bioethicist Leigh Turner has extensively investigated businesses promoting scientifically unsubstantiated stem cell treatments. His research uncovered hundreds of clinics advertising therapies for conditions ranging from joint pain to Alzheimer’s disease—despite a lack of credible evidence.

Some of these businesses learned to exploit ClinicalTrials.gov as a marketing platform, registering what appear to be clinical studies but are actually “pay‑to‑participate” procedures.

Turner and collaborators identified troubling patterns, including:

- Trials listed as “patient-funded” despite lacking regulatory authorization

- Studies charging participants but failing to disclose these costs on ClinicalTrials.gov

- Registrations that looked like proper clinical research yet operated as commercial funnels

The public is particularly vulnerable to such tactics. Many patients assume that if a study appears on ClinicalTrials.gov, it must be legitimate or overseen by government authorities. That is not the case. The site’s only formal warning reads:

“Listing of a study on this site does not reflect endorsement by the NIH.”

The Hidden Complexity Beneath the Surface

Even putting aside misuse, ClinicalTrials.gov is a complex and often messy dataset. Its underlying structured version, AACT [5], contains nearly 50 interconnected tables and hundreds of variables, each with its own submission rules, time‑dependent definitions, and formatting inconsistencies. Free‑text fields, missing data, and non‑standard condition or intervention names further complicate large‑scale analytics [6].

Figure 1. AACT database schema

These issues are common in healthcare datasets, but their impact can be amplified when the dataset is used for automated analysis, AI model training, or trend monitoring.

A deceptively simple example: is_fda_regulated_drug

One variable that appears straightforward—but is not—is is_fda_regulated_drug, which seems to indicate whether a study involves an FDA‑regulated drug product.

Through our own research at Polygon Health Analytics, we discovered that the reality is far more nuanced because the field’s availability and meaning have changed over time:

Before 2012

- No designated field existed to record FDA‑regulated drug status.

- Older records often display as NA, not because the answer was “no,” but because the field did not exist.

2012–2016

- ClinicalTrials.gov began voluntarily collecting several new “FDA regulatory” data elements as a pilot.

- Sponsors could optionally report FDA‑regulated drug/device status, IND/IDE availability, and U.S. manufacturing/export information.

September 2016

- HHS published the Final Rule (42 CFR Part 11), making these fields mandatory for new records beginning January 18, 2017.

January 2017 onward

is_fda_regulated_drugbecame required for new or migrated records.- Missing values were flagged as NA, but now NA could mean multiple things—missing information, non‑applicable, or pre‑rule legacy record.

Thus, a variable that appears binary (yes/no) actually encodes regulatory history, temporal context, and submission practices. Misinterpreting it may distort trial counts, bias inclusion criteria, or lead to faulty downstream analytics—especially for AI models trained on raw data.

Why Data Quality Must Be a First Principle

At Polygon Health Analytics, we emphasize that data quality is not a final cleanup step—it is a foundational design principle. Producing reliable analytics from ClinicalTrials.gov, AACT, or any biomedical dataset requires:

- Understanding how definitions and requirements change over time

- Interpreting fields within their regulatory and operational context

- Conducting variable‑level validation rather than relying on field names alone

- Recognizing when the data cannot support a given question

High‑quality data products demand more than clean tables—they require domain expertise, methodological rigor, and a commitment to detail.

Because in biomedical data, as in science itself, the devil always lives in the details.

References

[2] Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007

[3] Clinical Trials Registration and Results Information Submission

[5] AACT Database